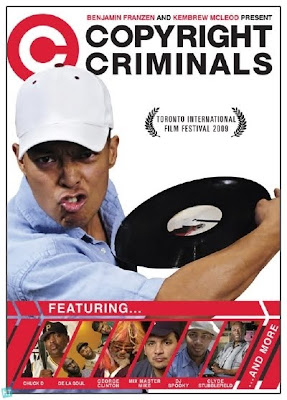

By now most music listeners have noticed that music is not as original as it used to be. The newest pop sensations are utilizing faint reminders of 80s songs gone by and hip-hop artists are blatantly featuring entire chunks of past tunes between their original beats and verses. While it’s universally accepted that this still counts as music, the documentary “Copyright Criminals” takes a look back at the history of sampling and the legal struggles taken to support a new breed of musicians.

Directors Benjamin Franzen and Kembrew McLeod rounded up an impressive roster of musicians, producers, entertainment lawyers and others in the music business as interview subjects exploring the copyright laws of sampling. While there is an attempt by the directors at showing all sides of the story, the finished product skews in favor of the musicians, a predictable bias. Utilizing visual techniques, familiar songs and an interesting topic, “Copyright Criminals” twists the typical documentary form, a task sometimes proven difficult in the “made-for-PBS” genre.

Straying from the monotony of the usual talking heads of documentaries, this film took a core message of the film’s music—“It’s all about collage”—and incorporated it with the film’s visuals. One montage in particular showed Clyde Stubblefield playing “Funky Drummer” on one side of the screen while a seemingly endless rotation of shots of groups such as Public Enemy, Beastie Boys, LL Cool J, Prince and more. This visually and musically shows Stubblefield’s importance to the world of sampling instead of just relying on a series of interviews to get his involvement across.

It may not have been in the director’s hands, but those representing the side of the law and the negative aspects of sampling came across as jaded by the industry. Producer Anthony Berman refers to sampling as a lazy artistic choice, an argument easily and almost immediately refuted by artists describing a tedious process of collecting and arranging samples that is anything but lazy. A stronger opposing view would have created more of an impact on how serious the conflict is.

Despite the lack of a strong opposition, the forces representing the pro-sampling crowd are entertaining and genuine. Checking in with some of the original sampling artists, such as De La Soul, reminds viewers where and how the technique started while up-and-coming artists shown in their creative habitats remind how the industry is changing and where the future of sampling is heading.

An entertaining and informative look into something affecting the music business daily, “Copyright Criminals” serves its purpose to educate without being boring. The lingering message of the film might make one stop and question the next sampling beat they come across and wonder who actually owns that sound.